Understanding Craniocervical Instability (CCI) and Atlanto-Axial Instability (AAI)

Medically Reviewed by Dr. Sony Sherpa, (MBBS)

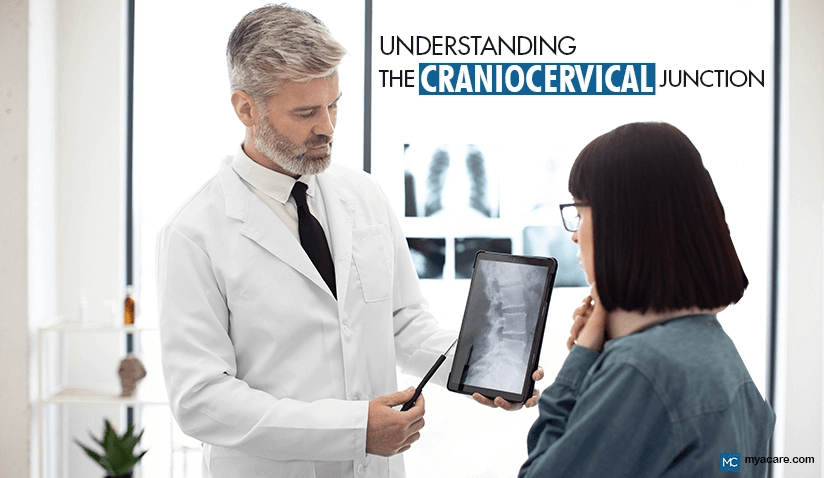

The craniocervical junction (the upper cervical spine) is a complex and vital body area responsible for head and neck stability. It comprises the skull, the first two vertebrae of the spinal column (C1 and C2), and the surrounding ligaments and muscles. Any instability in this area can lead to serious health issues, including craniocervical instability (CCI) and atlantoaxial instability (AAI).

This article explores the anatomy of the craniocervical junction, the types and causes of CCI and AAI, their symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Anatomy of the Craniocervical Junction

The craniocervical junction is a complex structure that connects the skull (C0) to the upper cervical spine (C1-C2). It is responsible for supporting the weight of the head in a way that enables a wide range of motion, including flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation.[1]

The prime components of the craniocervical junction include:

- The facet joints: The facet joints are small joints located on the back of the vertebrae that allow for movement and stability in the spine. In the craniocervical junction, the facet joints between the atlas (C1) and axis (C2) vertebrae allow for nodding and tilting of the head.

- The ligaments: These are powerful bands of tissue that connect bones and provide stability. The craniocervical junction contains several essential ligaments, including:

- Alar ligaments: The alar ligaments connect the odontoid process of the axis (C2) to the base of the skull (C0) and limit excessive head rotation at the atlantoaxial joint.

- Transverse ligament: The transverse ligament wraps around the odontoid process of the axis (C2). It holds the odontoid process in place and prevents it from compressing the spinal cord.

- Capsular ligaments: The capsular ligaments surround the facet joints between the atlas (C1) and axis (C2) vertebrae. They provide stability to these joints and limit excessive movement.

Secondary Affected Structures

CCI and AAI can lead to the compression of the brainstem, spinal cord, and vertebral artery, giving rise to many of the symptoms seen in those affected.

- The brainstem: The brainstem is a vital lower part of the brain that rests above the spinal cord. It controls many essential functions, including heart rate, breathing, and digestion. Instability in the craniocervical junction can place pressure on the brainstem, leading to serious neurological problems.

- The spinal cord: The spinal cord is a feedback hub for nerves that extend towards the periphery, connecting the brain to the rest of the body. Instability in the craniocervical junction can compress the spinal cord, resulting in weakness, pain, and numbness in the extremities.

- The dens: The odontoid process, or dens, is a bony projection on the axis (C2) vertebra that fits into a ring formed by the atlas (C1) vertebra. In CCI or AAI, it can protrude and contribute towards compressing nearby structures or the instability of the cervicocranial junction. A malformed dens may promote CCI or AAI.

- The vertebral artery: The vertebral artery supplies blood to the brain. Injury or instability in the craniocervical junction can compress the vertebral artery, reducing blood flow to the brain and causing dizziness, headaches, and stroke. This condition is known as Bow Hunter's syndrome.

Differentiating CCI from AAI

The atlantoaxial joint only refers to half of the craniocervical junction (C1 and C2), omitting the skull's (C0) involvement. This is why CCI and AAI are often discussed interchangeably. AAI is more likely to cause[2]:

- The dens or odontoid process (a small part of the atlantoaxial joint) to move backward towards the brainstem

- Brainstem compression

- Rotational dysfunction or inability to rotate the head, also known as Cock Robin syndrome

- Bow Hunter's syndrome (vertebral artery compression)

CCI is more likely to cause:

- Jugular outlet obstruction (neck vein compression)

- Basilar invagination, a condition where the top of the spine pushes upward into the base of the skull

Types and Causes of Craniocervical Instability and Atlanto-Axial Instability

There are three main types of craniocervical instability: ligamentous, osseous, and post-traumatic.

- Ligamentous instability occurs when the ligaments supporting the craniocervical junction are damaged or weakened. Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome can cause this manifestation.

- Osseous instability occurs when there is a structural issue with the bones in the craniocervical junction. Conditions such as fractures or congenital abnormalities are frequent causes. While Chiari malformation may co-occur with craniocervical instability, it is not a direct cause of osseous instability.

- Post-traumatic instability occurs after a traumatic injury, such as a car accident or a fall, that damages the structures in the craniocervical junction.

Several conditions and factors can contribute to the development of CCI and AAI. These include[3]:

- Physical Trauma: This includes injuries like car accidents, falls, or whiplash that damage the ligaments or bones in the craniocervical junction.

- Infection: Infections in the bones or tissues surrounding the craniocervical junction can cause inflammation and instability. Upper respiratory tract infections and tuberculosis can lead to CCI. Many neurological infections and chronic infectious illnesses can cause muscle weakness and even paralysis, which may contribute to CCI/AAI.

- Inflammatory Disease: Autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis can weaken the ligaments that support the craniocervical junction.

- Congenital Disorders: Conditions like Down's syndrome or Os odontoideum can cause malformations in the bones and ligaments of the craniocervical junction. Os odontoideum[4] is a spinal condition where the dens or odontoid process is abnormally small and separated from the rest of the vertebra, potentially causing instability in the upper neck. On the other hand, Chiari malformation, a congenital condition where part of the cerebellum extends downward into the spinal canal, does not directly cause craniocervical instability (CCI), but the two conditions can be linked under certain circumstances:

- Underlying Connective Tissue Disorders: Some patients with Chiari malformation have underlying connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). These disorders can cause ligament laxity, leading to craniocervical instability. In these cases, both Chiari malformation and CCI are secondary to the connective tissue disorder.

- Surgical Complications: Sometimes, after surgery to correct a Chiari malformation (such as posterior fossa decompression), patients may develop or worsen craniocervical instability due to changes in the support structures around the craniocervical junction.

- Secondary Degenerative Changes: Over time, abnormal pressure dynamics and anatomical changes caused by the Chiari malformation may exacerbate or contribute to instability in some patients, but this is not a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is an inherited disorder that primarily affects the body's connective tissues, weakening the ligaments in the craniocervical junction.

- Cancer: Tumors in or near the craniocervical junction can put pressure on the bones and ligaments, leading to instability. Common examples include hemangiomas (blood vessel and skin tumors) and cancerous bone cysts.

- Fluoroquinolones: This class of antibiotics has been linked to an increased risk of tendon ruptures and may also contribute to ligament damage in the craniocervical junction.

Symptoms of CCI and AAI

The symptoms of CCI and AAI can vary depending on the severity of the instability and the underlying cause. Some common symptoms include[5]:

- Pain in the neck

- Popping or clicking of the neck joints

- Hypermobility of the neck

- Migraines

- Blurred visions or seeing double

- Light sensitivity

- Loss of memory

- Dizziness or vertigo

- Tinnitus

- Trouble speaking, swallowing, eating, or breathing

- Sleep apnea and sleep-disordered breathing

- Sleep disturbances

- Autonomic Dysfunction

- Limb numbness or tingling

- Instability while walking

- Muscle weakness in limbs

- Lack of coordination

- Brain fog or inability to think clearly

- Chronic fatigue

Diagnosis of Craniocervical Instability

Diagnosing CCI and AAI can be difficult since the symptoms of CCI and AAI might mimic those of other conditions. However, a thorough evaluation that considers a patient's symptoms, manual tests performed by a doctor or therapist, and diagnostic imaging can help to increase the accuracy of diagnosis.

Diagnostic imaging tests helpful for diagnosing craniocervical instability include[6]:

- Dynamic Motion X-ray (DMX): This specialized X-ray captures images of the craniocervical junction in motion, which can help to identify instability that may not be apparent in static images.

- CT Scan with motion: Similar to DMX, a CT scan with motion can provide detailed images of the craniocervical junction in different positions.

- Static Upper Neck MRI: An MRI scan can create detailed cross-sectional images of the upper cervical spine's bones, soft tissues, and spinal cord.

- Dynamic MRI: A dynamic MRI can assess the movement of the craniocervical junction, similar to a DMX or CT scan with motion.

Treatment Options for Craniocervical Instability

Living with CCI and AAI can be challenging, yet with the right treatment and management, it is possible to live a full and active life. For the best results, it is crucial to work with a healthcare team that can find the best treatment plan for your specific needs.

The treatment and long-term outlook for CCI and AAI depend on the severity of the instability and the underlying cause.

Those with milder cases may find symptom resolution from physical therapy, pain control, or neck braces or collars for support and stability. There are also alternative therapies for CCI and AAI that may help with symptom management, such as chiropractic adjustments.

However, for more extreme instances, surgical procedures might be necessary to correct the instability.[7]

Non-Invasive Treatments

Intra-articular Facet Injections: Involves injecting a local anesthetic and steroid into the facet joints to reduce inflammation and pain.[8]

Posterior Prolotherapy: A non-surgical treatment that involves injecting a dextrose (irritant) solution into the ligaments and tendons in the craniocervical junction to stimulate healing and strengthen the area.[9] Evidence to support its efficacy is limited.

Physiotherapy

A physiotherapist can help those with CCI or AAI to learn how to maintain better posture and strengthen their neck muscles. They may also offer a neck brace to help the patient achieve the desired outcome.

Exercise for CCI can help strengthen the neck muscles and improve overall stability in the craniocervical junction.

A few simple exercises that may help include[10]:

- Gentle neck rotations

- Chin tucks

- Practicing yes and no neck motions

- Keeping the neck straight in a good posture

You should consult your physician before starting any of these exercises and stop if they cause pain.

Surgery

In severe cases, occipitocervical fusion surgery is necessary to stabilize the craniocervical junction. This involves fusing the vertebrae with screws, bolts, and rods to prevent movement and reduce pain.[11]

The surgery drastically limits the patient's range of motion. It is known to have several drawbacks and risks, such as cervical or cranial degeneration diseases, where nearby structures bear additional loads and are prone to degeneration over time. Other risks include bleeding and infection.

Can a Chiropractor Help with CCI and AAI?

Chiropractic care may help manage CCI and AAI symptoms by correcting spinal alignment issues and lowering pressure on the craniocervical junction. However, depending on the cause, it may also exacerbate symptoms.

It is essential to allow an expert to assess your case to determine which treatments can help remedy your spinal instability.

Latest Advancements in Treatment

Advancements in medical technology and research have led to new and innovative treatments for CCI and AAI. Some of the latest advancements include:

- Image-guided, Minimally Invasive Surgical Techniques: Image-guided technology allows for more precise and minimally invasive surgical approaches in CCI/AAI treatment. These techniques aim to minimize complications, reduce surgical trauma, and potentially shorten recovery times[12].

- Advances in Fusion Techniques: New surgical techniques and hardware designs are being developed to improve fusion success rates and reduce complications[13]. Some researchers also explore using 3D printing and patient-specific implants for more precise stabilization.

- Motion-Preserving Devices: Although traditionally, the goal has been to restrict movement in the area, there is interest in developing motion-preserving technology like artificial discs that maintain a greater range of motion while providing stability.[14]

Conclusion

Understanding craniocervical instability (CCI) and atlantoaxial instability (AAI) is essential for recognizing their impact on health. Many factors can contribute to CCI and AAI, and early diagnosis is key for effective management. With advancements in therapies and proper care, individuals with CCI and AAI can lead fulfilling lives. Raising awareness and promoting early intervention can improve outcomes and support those living with these conditions.

To search for the best Neurology Healthcare Providers in Croatia, Germany, India, Malaysia, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, the UAE, UK and the USA, please use the Mya Care search engine.

The Mya Care Editorial Team comprises medical doctors and qualified professionals with a background in healthcare, dedicated to delivering trustworthy, evidence-based health content.

Our team draws on authoritative sources, including systematic reviews published in top-tier medical journals, the latest academic and professional books by renowned experts, and official guidelines from authoritative global health organizations. This rigorous process ensures every article reflects current medical standards and is regularly updated to include the latest healthcare insights.

Dr. Sony Sherpa completed her MBBS at Guangzhou Medical University, China. She is a resident doctor, researcher, and medical writer who believes in the importance of accessible, quality healthcare for everyone. Her work in the healthcare field is focused on improving the well-being of individuals and communities, ensuring they receive the necessary care and support for a healthy and fulfilling life.

Sources:

Featured Blogs