Osteogenesis Imperfecta (Brittle Bone Disease): Causes, Treatment

Medically Reviewed by Dr. Sony Sherpa, (MBBS)

Fact Checked by Dr. Rae Osborn, Ph.D.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI) is a rare yet significant bone disorder, with a prevalence estimated at 1 in 10,000–20,000 live births worldwide. The prevalence of OI varies by population; however, both males and females are equally affected.

Awareness and early diagnosis of OI play a crucial role in improving patient outcomes. Awareness helps families and healthcare providers recognize the early signs, which is vital to ensuring that children with OI receive proper care and support. Early recognition allows for prompt management, physiotherapy, and supportive care to reduce fracture risk and enhance quality of life.

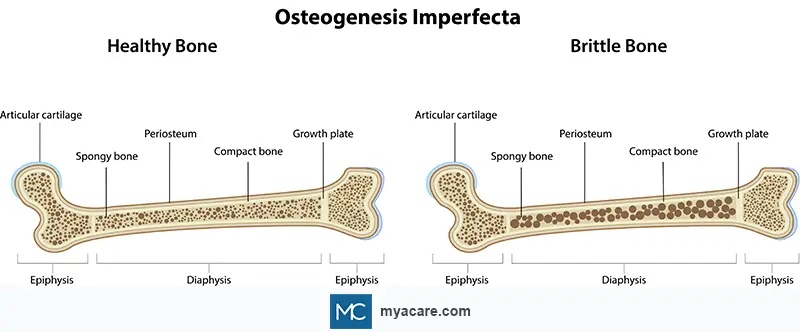

What Is Osteogenesis Imperfecta?

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetic disorder that affects the body’s ability to form strong bones, leading to frequent fractures and skeletal deformities. It is commonly known as “brittle bone disease” because bones break or crack easily, often from minor injuries or, in severe cases, without any apparent cause.

OI is not a single disease but rather a spectrum of disorders, ranging from mild forms with few fractures to severe, life-threatening types where fractures occur before birth. Medical experts have identified multiple types, traditionally eight (Types I–VIII), though newer classifications include more subtypes, based on genetic cause and clinical severity.

Causes and Risk Factors

Osteogenesis imperfecta is primarily caused by genetic mutations that affect collagen production. In most cases, mutations occur in one of two key genes: COL1A1 and COL1A2, which are responsible for encoding the alpha chains of type I collagen. These mutations disrupt collagen synthesis, leading to weak connective tissue and fragile bones. The defective collagen and resultant weakness in the connective tissues can also lead to joint laxity, dental problems (dentinogenesis imperfecta), hearing loss, and blue sclerae.

Risk Factors for Developing OI

Family history of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

In about 90% of OI cases, inheritance is autosomal dominant, meaning a single mutated copy from either parent can cause the condition. Children have a 50% chance of inheriting the disorder from an affected parent. Less commonly, certain OI types are autosomal recessive, requiring pathogenic variants in both gene copies.

De Novo Mutations

In many individuals, especially those with no family history of OI, the mutation occurs de novo, that is, spontaneously during early embryonic development.

Genetic Predisposition

Variations in collagen-related genes increase susceptibility to mild or moderate forms of OI. Mutations in genes such as CRTAP, P3H1, or IFITM5 have also been linked to rarer forms of the condition.

OI is purely genetic; environmental factors or lifestyle choices do not cause the disease. Understanding the genetic risk helps guide family counseling and early diagnosis in at-risk pregnancies.

Types of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

OI is grouped into several types, distinguished by the underlying genetic mutation, inheritance pattern, and clinical severity. Traditionally, four main types (I–IV, described by Sillence) were recognized. With advances in molecular genetics, this classification expanded to Types I–VIII. Today, 19 distinct types have been identified, including newly described dominant and recessive forms, reflecting both genotype and phenotype differences. Some sources report up to 22 types currently recognized.

Type I (Mild Form)

- Severity: The mildest and most common form of OI.

- Genetic Cause: Usually caused by a COL1A1 gene mutation, leading to reduced production of normal type I procollagen (needed to make proper collagen)

- Clinical Features:

- Bones fracture easily, but deformities are minimal.

- Normal or near-normal stature.

- Blue sclerae (bluish tint in the whites of the eyes).

- Possible hearing loss in adolescence or adulthood.

- Mild joint laxity and dental issues (dentinogenesis imperfecta) in some cases.

Type II (Perinatal Lethal Form)

- Severity: Most severe form, often lethal shortly after birth.

- Genetic Cause: Mutations in COL1A1 or COL1A2 that result in abnormal collagen structure.

- Clinical Features:

- Multiple fractures detected in utero or present at birth.

- Underdeveloped lungs and a small chest cavity.

- Severe bone deformities, rib fractures, soft skull, and short deformed limbs.

- Infants typically die from respiratory failure or complications at or soon after birth.

Type III (Severe, Progressively Deforming Form)

- Severity: The most severe form with expected survival beyond infancy.

- Genetic Cause: Mutations in COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes producing structurally defective collagen.

- Clinical Features:

- Frequent fractures starting at birth or early infancy.

- Severe bone deformities with progressive curvature of the spine scoliosis and kyphosis).

- Very short stature and triangular facial appearance.

- Blue or gray sclerae that may lighten with age.

- Hypermobile joints

- Respiratory problems and dentinogenesis imperfecta are common.

- Many patients are wheelchair-dependent by adolescence.

Type IV (Moderate Form)

- Severity: Moderate; between Types I and III.

- Genetic Cause: Usually due to mutations in COL1A1 or COL1A2, producing defective collagen with normal amounts.

- Clinical Features:

- Recurrent fractures and mild to moderate deformities.

- Normal or grey sclera color (unlike Type I).

- Possible short stature and mild bone curvature.

- May have dentinogenesis imperfecta.

- Life expectancy is typically near normal for mild illness.

Type V (Moderate, Non-Collagen Type)

- Severity: Moderate.

- Genetic Cause: Mutation in the IFITM5 gene, not in collagen genes.

- Clinical Features:

- Bone fragility similar to Type IV.

- Calcification of interosseous membranes (between forearm bones).

- Hypertrophic callus formation after fractures or surgery.

- No dentinogenesis imperfecta.

Type VI (Rare, Moderate Form)

- Severity: Moderate, similar to Type IV.

- Genetic Cause: Mutations in the SERPINF1 gene, affecting bone mineralization.

- Clinical Features:

- Normal collagen structure but defective mineralization of bone.

- Frequent fractures with slow healing.

- Characteristic “fish-scale” appearance of bone under a microscope.

Type VII and VIII (Recessive Forms)

- Severity: Moderate to severe, often resembling Type II or III.

- Genetic Cause:

- Type VII: Mutation in the CRTAP gene.

- Type VIII: Mutation in the P3H1 gene (LEPRE1).

- Both affect collagen modification rather than production.

- Clinical Features:

- Severe growth retardation.

- Short limbs, soft bones, and deformities.

- Fractures from birth or early infancy.

- Autosomal recessive; mutations must be inherited from each parent.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

The symptoms of osteogenesis imperfecta vary widely depending on the type and severity of the condition. While some people experience only occasional fractures, others may have severe deformities and complications affecting multiple body systems. Despite this variability, most individuals with OI share a few hallmark features linked to collagen abnormalities.

Frequent Bone Fractures

The most distinctive feature of OI is recurrent bone fractures, often from minimal trauma or even normal activities. In severe cases, fractures may occur before birth or during infancy. Over time, repeated breaks can cause bone deformities, curvature of the spine (scoliosis), and limb shortening.

Short Stature and Skeletal Deformities

Due to abnormal bone growth and repeated fractures, individuals often develop short stature, bowed legs, or curved spines. These deformities tend to worsen with age in more severe types such as OI Type III.

Loose Joints and Muscle Weakness

Collagen defects affect not only bones but also connective tissue throughout the body, resulting in joint laxity (looseness) and reduced muscle tone (hypotonia). This combination may contribute to delayed motor milestones in children.

Blue Sclera

A striking characteristic of OI is blue or grayish sclerae, giving the whites of the eyes a bluish tint. This occurs because the thin collagen layer in the sclera allows the underlying uvea to show through. The blue hue is most prominent in Type I OI and may fade with age.

Hearing Loss

Hearing impairment affects about 50% of adults with OI, usually appearing in early adulthood. This occurs due to otosclerosis, which is abnormal bone growth in the middle ear that restricts movement of the ossicles (tiny hearing bones). Sensorineural and mixed hearing loss may also occur due to inner ear damage.

Dental Problems

Dentinogenesis imperfecta, a common oral manifestation of OI, leads to discolored, translucent, or brittle teeth. The enamel may chip easily, and teeth can wear down prematurely. This is most common in Types III and IV, where collagen defects extend to dental structures.

Respiratory and Cardiovascular Problems

Defective collagen and skeletal deformities can affect both lung and heart function.

- Respiratory complications: Chest wall deformities and scoliosis reduce lung expansion, leading to restrictive lung disease and increased risk of respiratory infections. Severe OI can also cause underdeveloped lungs, particularly in infants.

- Cardiovascular issues: Some patients develop aortic root dilation or valvular heart disease, possibly linked to connective tissue weakness in the vessel walls. Regular monitoring is essential in moderate to severe OI.

Neurological Concerns

Chronic skeletal deformities may compress nerves or the spinal cord, leading to basilar invagination (upward displacement of the spine into the skull) or hydrocephalus in severe cases. Patients may experience headaches, neck pain, or coordination problems if the brainstem or spinal cord is affected.

Easy Bruising and Fragile Skin

Since collagen is essential for maintaining vascular integrity, individuals with OI may bruise easily and have thin, stiff skin. Wound healing may also be slower than normal.

Complications of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Beyond skeletal symptoms, OI can lead to long-term complications affecting overall health, mobility, and quality of life.

Scoliosis and Spinal Deformities

Scoliosis (curvature of the spine) is a common complication, particularly in Types III and IV. It can impair posture, mobility, and respiratory function if not managed early through bracing, physiotherapy, or surgery.

Reduced Mobility and Chronic Pain

Frequent fractures, deformities, and joint laxity often cause chronic pain and reduced physical endurance. Mobility aids, physiotherapy, and pain management are essential parts of long-term care.

Psychological and Social Impact

The visible deformities, frequent medical interventions, and physical limitations may lead to anxiety, depression, or social withdrawal, especially in children and adolescents. Emotional support and counseling play an important role in holistic care.

Pregnancy-Related Complications

Women with mild to moderate OI can become pregnant and carry a child successfully. However, pregnancy in OI requires specialized medical care.

- Risks: Increased likelihood of fractures during pregnancy or delivery due to added skeletal stress, respiratory compromise from rib deformities, and higher risk of preterm labor.

- Inheritance: Given its often autosomal dominant inheritance, OI carries a 50% transmission risk per pregnancy when a parent is affected.

Pregnancy and Osteogenesis Imperfecta

With careful planning and medical support, many women with OI can safely conceive and deliver healthy children. Key steps include pre-conception preparation, genetic counselling, and close monitoring throughout pregnancy and delivery.

Genetic Counselling and Testing

A genetic counsellor can provide information on OI genetics and available testing options. If the specific gene causing OI in the parent is identified, options such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) with pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT) or prenatal diagnostic testing may be available. These tests do not imply that pregnancy termination is necessary; rather, they provide useful information for planning, monitoring, and managing pregnancy and delivery.

Pre-Conception Planning

Before attempting pregnancy, women with OI are advised to consult both a bone specialist and an obstetric provider. Optimizing bone health — including adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding smoking — is essential. Use of bisphosphonates should be reviewed, ideally stopping them about a year before conception due to potential effects on the baby’s bones.

Pregnancy Monitoring

Women with OI may have additional considerations due to skeletal deformities, a history of fractures, or respiratory challenges. Close monitoring by a multi-disciplinary team, including obstetricians, bone specialists, and neonatologists, can help manage any complications. Prenatal assessments, such as ultrasound or diagnostic testing, can provide further information, though OI may not always be fully detectable in utero.

Delivery Planning

Mode of delivery should be individualized; studies show that a cesarean section does not reduce at-birth fracture rates compared with vaginal delivery. Cesarean section may be preferred to reduce fracture risk during childbirth.

Diagnosing Osteogenesis Imperfecta

The disorder is typically diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluation, medical history, genetic testing, and imaging studies. As symptoms can vary widely in severity, accurate diagnosis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving geneticists, orthopedic specialists, and radiologists. Early detection is key to effective management and family counseling.

Clinical Evaluation and Medical History

Diagnosis often begins with a thorough clinical assessment. Doctors evaluate:

- Frequency and cause of bone fractures, particularly when they occur with minimal trauma.

- Presence of blue sclerae, short stature, hearing loss, or dentinogenesis imperfecta.

- Family history of OI or other collagen disorders.

- Physical signs such as joint laxity, scoliosis, or deformities of the ribs and limbs.

A consistent pattern of these findings raises a strong suspicion of OI, especially in children with recurrent fractures and no evidence of metabolic or nutritional bone disease.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing provides a definitive diagnosis by identifying mutations in genes associated with OI, primarily COL1A1 and COL1A2.

- In mild and moderate cases, these mutations lead to reduced or defective type I collagen.

- In severe or recessive forms, genes such as IFITM5, CRTAP, or P3H1 may be involved.

Modern next-generation sequencing panels can detect both dominant and recessive mutations, confirming the diagnosis and guiding genetic counseling for families.

Bone Density Scans (DEXA)

A Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan measures bone mineral density, which is typically significantly reduced in OI. The scan helps evaluate fracture risk, track disease progression, and monitor the effectiveness of therapies such as bisphosphonates.

Collagen Analysis

Collagen analysis involves examining a skin biopsy or cultured fibroblasts to study collagen synthesis and structure.

- Abnormal collagen production, such as delayed secretion or reduced stability, supports the diagnosis of OI.

- This test is particularly useful when genetic testing is inconclusive or unavailable.

Imaging Studies

X-rays and other imaging techniques are crucial for assessing bone structure and detecting characteristic skeletal abnormalities.

- Findings may include:

- Multiple fractures at various stages of healing.

- Beaded ribs, a radiologic sign seen in infants with severe OI due to repeated rib fractures and callus formation.

- Bowed long bones, vertebral compression, and scoliosis.

- CT or MRI scans may be used to evaluate cranial or spinal abnormalities, especially in severe cases.

Prenatal Diagnosis

Osteogenesis imperfecta can be detected before birth, especially in families with a known history or genetic mutation.

- Ultrasound: Severe forms (Type II or III) can be identified in the second trimester, showing shortened, bowed limbs, skull deformities, or rib fractures.

- Genetic testing: Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis allows early DNA analysis for known OI mutations.

- 3D and 4D ultrasounds can enhance the visualization of fetal skeletal abnormalities.

Prenatal diagnosis enables early counseling and preparation for potential medical challenges after delivery.

Differential Diagnosis of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Several conditions can mimic the clinical features of osteogenesis imperfecta, but careful assessment helps distinguish them.

- Achondroplasia: Both OI and achondroplasia cause short stature, but achondroplasia is marked by disproportionate limb shortening due to cartilage growth defects, while OI is characterized by bone fragility and frequent fractures.

- Rickets and Osteomalacia: These disorders result from defective bone mineralization (often due to vitamin D deficiency), leading to soft bones and deformities. In contrast, OI stems from a genetic collagen defect that causes brittle bones and blue sclera.

- Osteoporosis: Although both conditions involve low bone density, OI typically appears in childhood with recurrent fractures and skeletal deformities, whereas osteoporosis is an acquired bone loss seen later in life.

- Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome (EDS): EDS and OI share connective tissue abnormalities, but EDS primarily causes joint hypermobility and fragile skin, while OI mainly affects bone strength.

- Child Abuse: Repeated fractures in children with OI can be mistaken for abuse. However, features such as blue sclera, dentinogenesis imperfecta, and a positive family history help clarify the diagnosis.

Other rare disorders with overlapping features include Cole–Carpenter Syndrome, Osteoporosis–Pseudoglioma Syndrome, and Bruck Syndrome, all of which involve congenital bone fragility or deformities.

Treatment of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Medications

The main goal of treating Osteogenesis Imperfecta is to strengthen bones and reduce the risk of fractures. The most commonly used medicines are bisphosphonates, such as pamidronate and zoledronic acid. These drugs can help increase bone density and lower the chance of breaking bones.

For adults with OI, there are some newer options under consideration:

- Teriparatide – A medicine similar to parathyroid hormone that can help increase bone density in adults with Type I OI. Its benefits are less clear for people with more severe forms, like Types III and IV.

- Denosumab – An investigational drug that may improve bone density in some cases. However, research is still limited, especially on whether it actually reduces fractures. There is also a risk of high calcium levels if treatment is stopped suddenly.

These newer treatments are usually considered carefully by specialists and may be used when standard therapies are not enough or for specific patient situations.

Surgery

Surgical intervention may be required to correct bone deformities, stabilize fractures, or improve mobility. Intramedullary rodding (insertion of metal rods within long bones) helps strengthen weak bones and prevent recurrent fractures.

Dental, Hearing, and Vision Care

Dental issues such as dentinogenesis imperfecta can be managed through crowns and other restorative dental procedures. For otosclerosis, hearing aids may help; severe hearing loss may warrant a cochlear implant. Regular vision checks are also advised for scleral thinning and myopia.

Physical and Occupational Therapy

Physical therapy helps maintain muscle strength, improve balance, and reduce fracture risk through safe, low-impact exercises such as swimming. Occupational therapy supports daily functioning and adaptation to physical limitations.

Bracing and Assistive Devices

Braces, walkers, and customized mobility aids help enhance independence and reduce injury risk.

Lifestyle Management

Adequate calcium and vitamin D can help maintain healthy bones. Avoiding high-impact activities and maintaining a safe environment are crucial for minimizing falls and fractures.

Is There a Cure for Osteogenesis Imperfecta?

Currently, there is no cure for OI. At present, treatment emphasizes symptom relief and quality-of-life support. Advances in genetics and stem cell research may enable the development of future therapies.

Living with OI: Long-Term Management

Long-term care requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving orthopedists, endocrinologists, physiotherapists, audiologists, and genetic counselors. Regular follow-ups help monitor bone density, manage pain, and address new fractures or deformities. Psychological support can also help individuals cope with physical limitations and social challenges.

OI cannot be prevented, but genetic counseling helps at-risk families understand inheritance patterns and options for prenatal diagnosis.

Prognosis and Outlook

The outlook varies by OI type:

- Mild Forms (Type I): Normal or near-normal life expectancy with few complications.

- Severe Forms (Type II): Often fatal in infancy due to respiratory complications and bone fragility.

- Moderately Severe Forms (Type III & IV): Life expectancy may be reduced, but survival into adulthood is common with proper management. Life expectancy is often shortened for type III but normal for type IV. Quality of life depends on mobility, fracture frequency, and access to multidisciplinary care.

When to See a Doctor

Seek medical advice if you or your child experience:

- Recurrent or unexplained fractures

- Symptoms of OI in infancy (e.g., blue sclera, limb deformities)

- Family planning concerns or known OI gene mutations

- Signs of a cold, such as chills or fever

Prompt diagnosis and management can lead to better long-term outcomes.

Advances in Research and Future Treatments

Research into osteogenesis imperfecta is rapidly evolving, with scientists exploring therapies that go beyond symptom management to target the root genetic causes of the condition.

Gene Therapy

Gene therapy targets the faulty genes driving abnormal collagen production, primarily COL1A1 and COL1A2, to correct or replace them. Early laboratory and animal studies have shown potential in using viral vectors to deliver healthy gene copies or silence the defective ones, paving the way for long-term correction of bone fragility.

Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine

Stem cell–based treatments are being investigated to restore normal collagen synthesis. Researchers are experimenting with mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation, which can introduce healthy cells capable of producing normal type I collagen. Preliminary clinical trials in infants and children have shown encouraging improvements in bone density and growth rates.

Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies

Several clinical trials are evaluating novel medications that promote bone formation or reduce resorption, such as sclerostin inhibitors and TGF-β pathway modulators. Emerging gene-editing platforms, including CRISPR, are being studied for correcting mutations at the DNA level. Although these therapies remain experimental, they represent promising steps toward disease-modifying treatments for OI in the future.

To search for the best Orthopedics Healthcare Providers in Croatia, Germany, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, the UAE, UK, and the USA, please use the Mya Care search engine.

To search for the best healthcare providers worldwide, please use the Mya Care search engine.

The Mya Care Editorial Team comprises medical doctors and qualified professionals with a background in healthcare, dedicated to delivering trustworthy, evidence-based health content.

Our team draws on authoritative sources, including systematic reviews published in top-tier medical journals, the latest academic and professional books by renowned experts, and official guidelines from authoritative global health organizations. This rigorous process ensures every article reflects current medical standards and is regularly updated to include the latest healthcare insights.

Dr. Sony Sherpa completed her MBBS at Guangzhou Medical University, China. She is a resident doctor, researcher, and medical writer who believes in the importance of accessible, quality healthcare for everyone. Her work in the healthcare field is focused on improving the well-being of individuals and communities, ensuring they receive the necessary care and support for a healthy and fulfilling life.

Dr. Rae Osborn has a Ph.D. in Biology from the University of Texas at Arlington. She was a tenured Associate Professor of Biology at Northwestern State University, where she taught many courses to Pre-nursing and Pre-medical students. She has written extensively on medical conditions and healthy lifestyle topics, including nutrition. She is from South Africa but lived and taught in the United States for 18 years.

References:

Featured Blogs