Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS): A Comprehensive Overview

Medically Reviewed by Dr. Rae Osborn, Ph.D. - June 14, 2024

Young Fit Female Syndrome and Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome

Distinguishing Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome from Sleep Apnea

Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) is a sleep disorder that, despite its significant impact on health and quality of life, remains largely under the radar. It is characterized by increased resistance in the upper airway during sleep, which leads to sleep fragmentation and a host of daytime symptoms without the hallmark apneas or hypopneas associated with its close relative, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

The prevalence of UARS is not fully known, but it is believed to affect a considerable number of individuals, many of whom are unaware of their condition. This lack of awareness contributes to the disorder's misunderstood nature, as symptoms can often be attributed to stress, anxiety, or other health issues, delaying proper diagnosis and treatment.

The public and medical professionals need to be aware of the benefits of early diagnosis and effective management of UARS, which can greatly enhance a person's quality of life, general health, and sleep.

The first indications and signs of UARS were first noticed in children in the 1980s. However, Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome was first identified and described in the early 1990s by sleep researchers and clinicians who observed patients with unexplained daytime sleepiness and fatigue that did not meet the criteria for obstructive sleep apnea. These patients showed evidence of increased effort to breathe during sleep, leading to arousal and fragmented sleep, but without significant apneas or hypopneas.

Young Fit Female Syndrome and Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome

Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS), often dubbed "Young, fit, female syndrome," is characterized by its prevalent occurrence among healthy, young, and physically active women. While the risk of developing UARS can increase with age due to factors like decreased muscle tone and increased fat deposition around the airway, it can present at any age and in individuals who might not exhibit typical risk factors seen in other airway resistance disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea.

Certain younger populations have exhibited UARS, even though they lack the conventional risk factors associated with obstructive sleep apnea, such as marked overweight or being of older age. This demographic distinction contrasts sharply with the typical profile of those diagnosed with OSA, who are frequently older, male, and may have a higher body mass index (BMI). The term "Young, fit, female syndrome" not only highlights the shared traits of many UARS sufferers but also underscores the distinctiveness of its presentation and the diagnostic complexities it poses.

Why UARS Goes Undiagnosed

Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) is characterized by subtle, often overlooked symptoms such as a disturbed sleep pattern and fatigue, leading to its frequent under-diagnosis. Unlike the more recognized Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), UARS sometimes lacks obvious signs like loud snoring, contributing to a lack of awareness among both healthcare providers and the public.

This, coupled with a historical focus on sleep disorders in overweight, middle-aged men, has delayed the identification and understanding of UARS, particularly among young, fit women. Recognizing UARS as a distinct condition significantly improves the chances of diagnosis and treatment, addressing a critical gap in sleep disorder awareness and care.

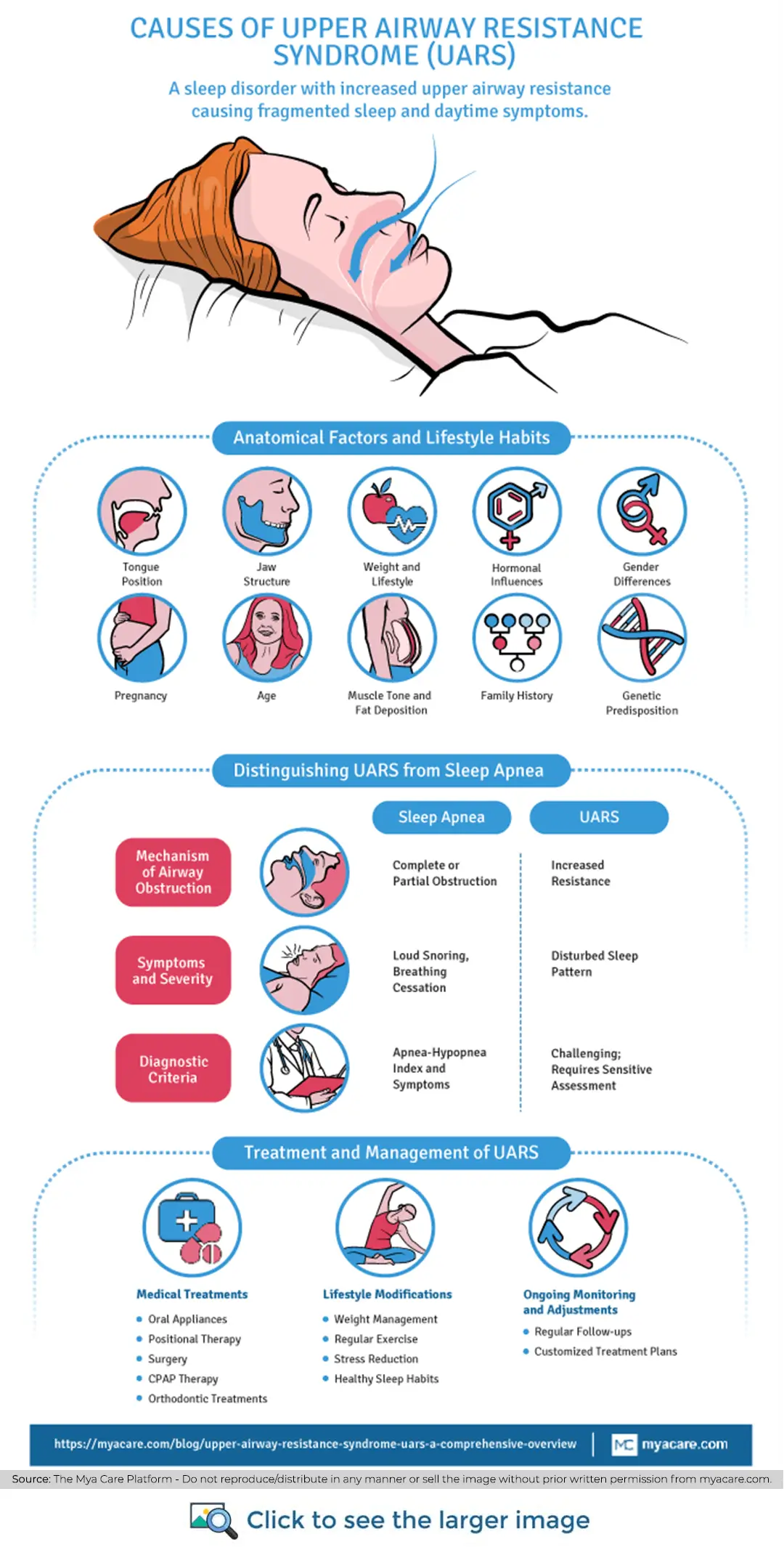

Distinguishing Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome from Sleep Apnea

Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) are both sleep-related breathing disorders, but they present differently, have varying diagnostic criteria, and may affect different populations. Here's a breakdown of the key differences between the two:

Mechanism of Airway Obstruction

- UARS: This disorder is characterized by increased resistance in the upper airway that does not necessarily lead to apnea (cessation of breathing) or hypopnea (reduced breathing). The resistance increases the work of breathing, causing arousal from sleep that fragments sleep architecture, even though the airway does not fully close.

- OSA: This involves complete or partial obstruction of the airway, leading to apnea or hypopnea. This obstruction decreases blood oxygen levels and causes significant sleep fragmentation due to the arousal needed to reopen the airway.

Symptoms and Severity

- UARS: Symptoms often include a disturbed sleep pattern, daytime fatigue, cognitive impairment, and, in some cases, symptoms similar to fibromyalgia. Snoring may be less pronounced than in OSA, and the episodes of increased breathing effort are less likely to be noticed by a partner.

- OSA: Characterized by loud snoring, observed episodes of breathing cessation, gasping or choking for air during sleep, significant daytime sleepiness, and morning headaches. The symptoms are generally more noticeable to others.

Diagnostic Criteria

- UARS: Diagnosing UARS is more challenging because while standard sleep studies (polysomnograms) that measure apneas and hypopneas sometimes do indicate UARS, they may not always capture the subtle increases in airway resistance and associated arousals. It often requires more sensitive measurements, such as esophageal pressure monitoring, to detect the increased effort to breathe.

- OSA: This disorder is diagnosed based on the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep (Apnea-Hypopnea Index, or AHI), along with symptoms of daytime sleepiness. AHI is a clear and widely accepted diagnostic metric.

Population Affected

- UARS: While UARS can affect individuals of any age, it has been observed in some younger populations who do not typically exhibit risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea, such as significant overweight or advanced age. This has led to occasional references to UARS in younger, physically fit individuals. However, this is not universally accepted as the typical demographic profile for UARS.

- OSA: Although more commonly associated with overweight or obese individuals and prevalent in men, OSA could also affect people who have a normal BMI. Physical conditions such as a naturally smaller airway, retrognathia, palate with a high arch, swollen tonsils, or micrognathia can contribute to airway narrowing which can lead to OSA. The smaller lower jaw in a person with micrognathia causes their tongue to fall backward, obstructing their airway and exacerbating their sleep apnea symptoms.

Weight Factors

- UARS: Weight is less of a defining factor, and many individuals with UARS are of normal weight. The condition is more related to the structure and function of the airway rather than body mass.

- OSA: There is a strong correlation between obesity and increased neck circumference, as excess weight can contribute to the mechanical obstruction of the airway during sleep.

Mechanism of UARS

Understanding these differences is crucial for the appropriate diagnosis and treatment of these conditions. While both UARS and OSA disrupt sleep and have significant health implications, their management strategies may differ due to the underlying mechanisms, diagnostic challenges, and patient profiles associated with each disorder.

The mechanism behind Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) involves a subtle yet significant disturbance in the respiratory process during sleep, which does not necessitate the complete closure of the airway, distinguishing it from Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA).

Key structures such as the uvula, soft palate, and epiglottis play crucial roles in this process. Normally, they help to facilitate smooth airflow into the lungs. However, in individuals with UARS, these tissues can contribute to airway narrowing. For instance, the soft palate or uvula may become more lax and encroach into the airway space, or the tongue may fall back towards the throat, especially in certain sleeping positions.

Hence, the airways narrow but do not fully close, leading to increased resistance against airflow. This resistance forces the body to exert more effort to breathe, disrupting the natural rhythm of breathing and fragmenting sleep.

However, this partial obstruction does not lead to the hallmark apneas (complete cessation of breathing) of OSA but results in a significant effort to maintain adequate ventilation during sleep.

The body's response to this increased breathing effort is often subtle, involving micro-arousals—brief awakenings that are usually too short to be remembered but sufficient to disrupt the sleep cycle. These disruptions prevent the individual from achieving deep, restorative stages of sleep, leading to symptoms of daytime fatigue, cognitive difficulties, and a disturbed sleep pattern. This cycle of increased respiratory effort and sleep fragmentation is at the core of UARS, impacting sleep quality and overall health without the complete airway blockages seen in OSA.

Causes

The causes of Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) are multiple, involving anatomical factors, lifestyle habits, and physiological conditions that contribute to the narrowing of the airway during sleep.

Anatomical Factors and Lifestyle Habits

- Tongue Position: A common anatomical cause is the tongue falling back towards the throat during sleep, which can block the airway and increase resistance to airflow.

- Jaw Structure: Conditions like micrognathia (a small jaw) or retrognathia (a receding jaw) can also predispose individuals to UARS by reducing the size of the airway.

- Weight and Lifestyle: While UARS can affect individuals of any weight, excessive weight can exacerbate the condition by adding pressure on the neck and airway. Lifestyle habits such as alcohol consumption and sedentary behavior can further influence muscle tone and airway patency.

Gender and Hormonal Influences

- Gender Differences: Studies suggest that UARS might be more prevalent in women, particularly those in their premenopausal and perimenopausal stages. This is possibly due to hormonal variations that affect muscle tone in the airway and breathing patterns. Estrogen and progesterone have been shown to play roles in maintaining airway patency. Fluctuations in these hormones can lead to increased airway resistance.

Pregnancy: Pregnancy is another condition that can increase a woman's risk of developing UARS. Hormonal changes, increased weight, and the upward pressure of the enlarging uterus on the diaphragm can all contribute to narrowed airways and increased breathing effort during sleep.

Age

As with many sleep-related breathing disorders, the risk of developing UARS can increase with age due to factors such as diminished muscle tone and greater fat accumulation around the airway. However, UARS can present at any age and in people who might not exhibit typical risk factors seen in other airway resistance disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea.

Family History

Genetics can play a role in the development of UARS. A family history of sleep disorders, including UARS and OSA, may predispose individuals to similar conditions. This genetic predisposition can be due to inherited anatomical features, such as the structure of the jaw, tongue size, and the overall shape of the airway, which can affect airway patency.

Symptoms

Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) mimics the sleep disorder symptoms, such as obstructive sleep apnea, but without noticeable apneas or loud snoring. The symptoms of UARS can seriously affect daily functioning and overall quality of life. Individuals with UARS may experience a range of symptoms, including:

- Excessive Daytime Sleepiness: Despite getting a full night's sleep, individuals with UARS often struggle with overwhelming sleepiness during the day, which can affect their productivity, mood, and overall quality of life.

- Fatigue: A pervasive sense of tiredness or lack of energy that is not relieved by sleep. It can be challenging to finish everyday chores when you're physically and mentally exhausted.

- Morning Headaches: Due to their disrupted sleep patterns and low oxygen levels during the night, a lot of patients with UARS wake up with headaches.

- Cognitive Difficulties: Impaired memory, attention, and executive function are common, as the disturbed sleep pattern affects the brain's ability to process and store information efficiently.

- Difficulty Concentrating: Insufficient sleep can cause issues with concentration and focus, which can impair productivity at work or school.

- Disturbed or Poor Sleep: Despite spending an adequate amount of time in bed, individuals with UARS often experience disturbed sleep. Individuals might experience trouble falling asleep, waking up multiple times during the night, or both.

These symptoms can lead to significant daytime impairment and may increase the risk of accidents, decrease work or academic performance, and negatively impact personal relationships.

Complications

Untreated Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) can lead to a variety of long-term health complications, underscoring the importance of timely diagnosis and management. While UARS might seem less severe than obstructive sleep apnea due to the lack of significant oxygen desaturation, its impact on sleep quality and overall health can be profound. Here are some of the potential health consequences of untreated UARS:

Heart Disease

The increased effort to breathe and frequent arousals associated with UARS can lead to fluctuations in blood pressure and increased heart rate, placing stress on the cardiovascular system. Over time, this can contribute to the development of heart disease.

Stroke

The chronic sleep disruption and associated cardiovascular strain linked with UARS may elevate the risk of stroke. The mechanisms include increased blood pressure and the potential for the formation of blood clots due to changes in blood flow dynamics.

Diabetes

Sleep disturbances and the resultant stress on the body can affect glucose metabolism, leading to insulin resistance-a risk factor for type 2 diabetes.

Depression

The chronic fatigue and sleep disruption caused by UARS can significantly impact mental health, potentially leading to or exacerbating depression. There is a well-established link between sleep quality and mental health, with poor sleep being both a cause and consequence of depressive disorders.

Insomnia

- Individuals with UARS often experience difficulty falling and staying asleep due to the frequent arousals caused by increased airway resistance. This can lead to a pattern of insomnia, further degrading sleep quality and exacerbating daytime symptoms.

High Blood Pressure

- The repeated arousals and sympathetic nervous system activation that occur with UARS can lead to chronic increases in blood pressure, known as hypertension. Over time, this can damage the cardiovascular system and increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Cognitive Decline

The fragmented sleep and reduced sleep quality associated with UARS can impair cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, and problem-solving skills. In the long-term, this may contribute to cognitive decline and increase the risk of dementia.

These possible side effects emphasize how important it is to identify and treat UARS. By addressing the condition early, individuals can mitigate these risks and improve both their sleep quality and overall health outcomes.

Diagnosis

A combination of clinical assessment and specialized sleep studies is used to diagnose Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS). Given the subtlety of UARS symptoms and the lack of significant oxygen desaturation that distinguishes it from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a thorough diagnostic approach is crucial. Here's an overview of the diagnostic process for UARS:

Sleep Studies and Home Monitoring Devices

- Polysomnography (PSG): This in-lab sleep study is the gold standard for diagnosing sleep disorders. For UARS, polysomnography tracks a wide range of physiological parameters throughout the night, including brain waves (to determine sleep stages), blood oxygen levels, heart rate, breathing patterns, and eye and leg movements.

While PSG is effective in diagnosing OSA by measuring apneas and hypopneas, diagnosing UARS requires careful analysis of the data to identify increased respiratory effort and arousal from sleep without significant apneas or hypopneas.

- Home Sleep Apnea Testing (HSAT): Some home monitoring devices are designed to measure parameters similar to polysomnography, though they are generally less comprehensive. While convenient, HSAT may not always capture the subtle breathing disturbances and arousals typical of UARS, making it less reliable for diagnosing this condition.

Physical Examinations

- Clinical Evaluation: A detailed medical history and physical examination are critical components of the diagnostic process. Healthcare providers will look for symptoms consistent with UARS, such as disturbed sleep, daytime fatigue, and cognitive difficulties, and may assess anatomical features that could contribute to airway resistance, such as nasal congestion, the size of the tonsils, the position of the jaw, and the structure of the palate.

- Nasal Airway Examination: Evaluating the nasal airway for obstructions or anatomical variations that could contribute to increased airway resistance.

- Oropharyngeal Examination: Inspecting the throat for enlarged tonsils, adenoids, or other features that might narrow the airway.

Additional Considerations

For a definitive diagnosis of UARS, healthcare providers may also consider the patient's response to trial treatment, such as the use of a CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) machine, to see if symptoms improve, which can further support the diagnosis.

Given the challenges in diagnosing UARS, a multidisciplinary approach involving sleep specialists, otolaryngologists (ENT doctors), and sometimes dentists specializing in sleep medicine can be beneficial. A more precise diagnosis and successful treatment plan result from this comprehensive approach, which makes sure that all possible contributing factors are taken into account.

Treatment and Management of Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS)

Managing UARS effectively requires a personalized approach, combining medical treatments, lifestyle modifications, and potentially surgical interventions. The goal is to reduce airway resistance during sleep, thereby improving sleep quality and reducing daytime symptoms.

Medical Treatments

- Oral Appliances: These devices are designed to advance the position of the jaw or tongue, thereby widening the airway and improving airflow during sleep. They are particularly useful for patients with mild to moderate UARS and those who prefer not to use CPAP therapy. Pros include ease of use, portability, and being less intrusive than CPAP. Cons can include discomfort, jaw pain, and potential long-term dental changes. Tailoring the appliance to the individual’s specific anatomical needs is crucial for effectiveness and comfort.

- CPAP Therapy: Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) therapy remains a cornerstone in the treatment of sleep-related breathing disorders, including UARS. CPAP keeps the airway open while you sleep by continuously supplying air through a mask. Benefits for UARS patients include significant improvement in sleep quality and reduction in daytime fatigue. Risks or drawbacks include discomfort wearing the mask, nasal congestion, and the need for nightly use to maintain benefits. The therapy requires customization of the mask fit and pressure settings for each patient.

- Orthodontic Treatments: These interventions aim to address underlying anatomical causes of UARS, such as a narrow palate or misaligned jaw, through devices like braces or expanders. Pros include long-term resolution of airway restrictions and improvement in oral health. Cons involve the duration of treatment, potential discomfort, and cost. These treatments are tailored based on individual orthodontic assessments.

- Surgery: Procedures such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy can be effective in removing obstructions in the airway. Surgery may also involve correcting structural abnormalities contributing to airway narrowing. Benefits include potentially permanent solutions to airway obstruction. Risks include surgical complications, recovery time, and the possibility of recurrence if not all contributing factors are addressed.

- Positional Therapy (PAP): This involves strategies to encourage sleeping in positions that minimize airway obstruction, such as on the side. Special devices can prevent back sleeping. It is a supplementary approach, often used alongside other treatments.

Lifestyle Modifications

- Weight Management: Airway resistance can be decreased by keeping weight at a healthy level by reducing fat deposits around the neck.

- Regular Exercise: Physical activity can improve muscle tone, including the muscles around the airway, and overall health, contributing to better sleep quality.

- Healthy Sleep Habits: Sleep quality can be improved by creating a regular sleep routine, making sure the bedroom is peaceful, and abstaining from stimulants like alcohol and coffee right before bed.

- Stress Reduction: Yoga or meditation can help reduce tension and encourage relaxation and better sleep.

Ongoing Monitoring and Adjustments

The effectiveness of treatment for UARS often requires ongoing monitoring and adjustments by healthcare providers. Regular follow-ups can ensure that the chosen treatments remain effective and are adjusted as needed to meet changing needs or address any emerging issues. Customizing the treatment plan to the individual’s specific symptoms, lifestyle, and preferences is key to managing UARS successfully, reducing its impact on daily life, and improving overall health and well-being.

Can You Prevent UARS?

Preventing Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) can be challenging due to its multifactorial nature involving anatomical, genetic, and lifestyle factors. However, addressing modifiable risk factors may help reduce the likelihood of developing UARS or mitigate its severity. Strategies such as maintaining a healthy weight, ensuring regular physical activity, and adopting good sleep hygiene can be beneficial. Additionally, early identification and management of anatomical factors predisposing to UARS, like nasal congestion or jaw misalignment, through medical or dental interventions can also play a preventive role.

Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome and Anxiety

The relationship between UARS and anxiety is bidirectional. The chronic sleep disruption and daytime fatigue associated with UARS can exacerbate anxiety symptoms, while anxiety can contribute to sleep disturbances, creating a vicious cycle. For some people, identifying and treating UARS can result in notable reductions in anxiety, underscoring the significance of taking sleep problems into account when making a differential diagnosis of anxiety disorders.

Future of UARS Research and Treatment

Ongoing research in the field of sleep medicine is continuously unveiling new insights into UARS, its pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Advancements in diagnostic technologies, such as more sensitive and user-friendly home sleep monitoring devices, are improving our ability to detect subtle abnormalities in breathing and arousal patterns associated with UARS. These technologies hold promise for earlier and more accurate diagnosis of the condition, potentially in the comfort of the patient's home.

In terms of treatment, the future looks promising with the development of novel therapeutic approaches and refinements to existing treatments. Personalized medicine, informed by genetic markers and individual risk profiles, may offer tailored treatment strategies that optimize outcomes. Innovations in oral appliance design, surgical techniques, and CPAP technology are aimed at increasing effectiveness, comfort, and patient compliance. Moreover, interdisciplinary approaches that integrate lifestyle modifications, psychological support, and medical management are becoming increasingly recognized as essential for comprehensive care.

Additionally, research into the neural and hormonal mechanisms underlying UARS could lead to new pharmacological treatments targeting the root causes of the syndrome. The exploration of neurostimulation techniques, which aim to maintain airway patency by stimulating muscle tone during sleep, also offers new hope.

Personalized, adaptable solutions that improve patient outcomes could be provided by the possible integration of AI and machine learning algorithms with diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, further revolutionizing UARS management As research progresses, the future of UARS treatment holds the promise of more effective, accessible, and personalized care, significantly improving the quality of life for those affected by this challenging sleep disorder.

Conclusion

Despite being quite common, UARS lacks awareness and is challenging to diagnose, due to the similarity of symptoms with a few sleep disorders. It is important to recognize the signs and diagnose UARS early since, if left untreated, it can lead to mood disorders, cognitive impairment, chronic fatigue, and raises the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

To search for the best Pulmonary and Respiratory Medicine healthcare providers in Germany, India, Malaysia, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, the UAE, the UK and The USA, please use the Mya Care Search engine

To search for some of the best Ear, Nose Throat (ENT) worldwide, please the Mya Care search engine

To search for the best doctors and healthcare providers worldwide, please use the Mya Care search engine.

The Mya Care Editorial Team comprises medical doctors and qualified professionals with a background in healthcare, dedicated to delivering trustworthy, evidence-based health content.

Our team draws on authoritative sources, including systematic reviews published in top-tier medical journals, the latest academic and professional books by renowned experts, and official guidelines from authoritative global health organizations. This rigorous process ensures every article reflects current medical standards and is regularly updated to include the latest healthcare insights.

Dr. Rae Osborn has a Ph.D. in Biology from the University of Texas at Arlington. She was a tenured Associate Professor of Biology at Northwestern State University, where she taught many courses to Pre-nursing and Pre-medical students. She has written extensively on medical conditions and healthy lifestyle topics, including nutrition. She is from South Africa but lived and taught in the United States for 18 years.

References:

Featured Blogs